What if the stat revolution made us blind to greatness?

The Gospel of Moneyball

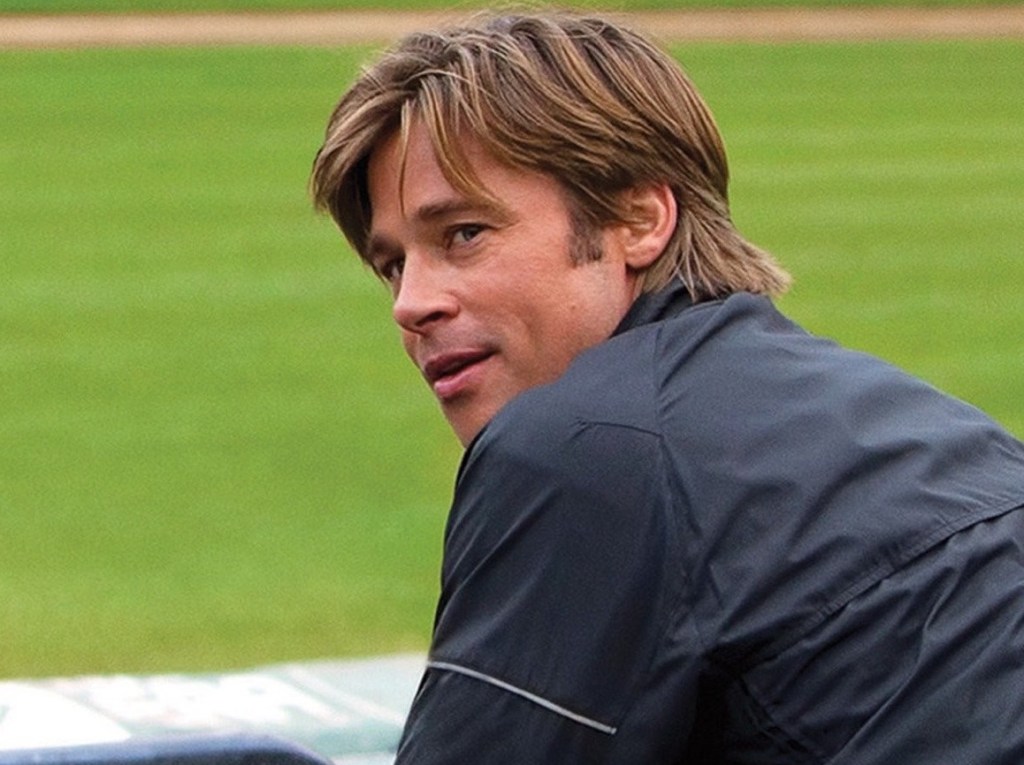

In 2002, a small-market team with a slashed budget and no household stars won 103 games. Billy Beane and the Oakland A’s—immortalized in Moneyball—rewrote the book on baseball evaluation. Walks became sacred. On-base percentage became gold. Personality became a liability.

And worst of all: emotion was eliminated from the equation.

The movement that followed was a revelation—and a revolution. It made the game smarter. More objective. More optimized.

And then a big ol’ Hollywood movie with a major heart-throb and a comedic icon at the forefront of it turned what is possibly the most boring advancement in baseball scouting into a cultural sensation.

Period. Not ‘since’ anything. Just the most boring.

Top 5 Scouting Advancements in 100+ Years of the MLB that are More Fun than “Moneyball”

Here are some advancements to scouting that likely improved the way scouts operated after its introduction:

- Abacus – Man cannot calculate exit velocity with merely his hands.

- Microsoft Excel – I mean the only thing as boring than the actual statistic is the system that was used to come up with the statistic.

- Copying machine / Mimeograph – creating a player report sheet from scratch every time just gets old at a certain point.

- Car – it was long past due to hang up the spurs and stop cleaning up after our modes of transportation.

- Radar gun – I mean, what did you think was going to be at #1, Microsoft Excel’s Clippy integration? Nope. The cops use these things. Name another police technology that we use in sports (other than mace in WWE).

- Slow-motion video – there’s no better way to watch an ump get a call wrong for the sixth time than a little bit of slow-mo.

But I digress…

Something else happened, too.

We stopped trusting our eyes. We stopped trusting our gut. And worst of all, we started trusting the model too much.

The result? Players who burned brighter than data could measure—players who didn’t fit, but couldn’t be stopped—began to fall through the cracks. In a world run by spreadsheets, outliers became risks. And risk became invisible.

What Moneyball Gets Wrong

Moneyball wasn’t a lie—it was a tool. It helped teams find value where others weren’t looking. It identified overlooked contributors and cut fat from bloated rosters.

But it also made a dangerous promise: that if you just trust the data, the truth will reveal itself.

Only… it doesn’t.

The model can’t measure:

- Grit after your mom dies

- Film obsession at 3 a.m.

- Rage after a blown call

- Clutch adrenaline in front of 50,000

- The chip on your shoulder from a lifetime of being underestimated

Moneyball sees inputs. But greatness often lives in spite of those inputs.

Outliers don’t project. They detonate.

8 Players the Model Would’ve Missed

Let’s name names.

These are players who would’ve been undervalued—or missed completely—if they were judged only by Moneyball-style metrics in today’s pipeline.

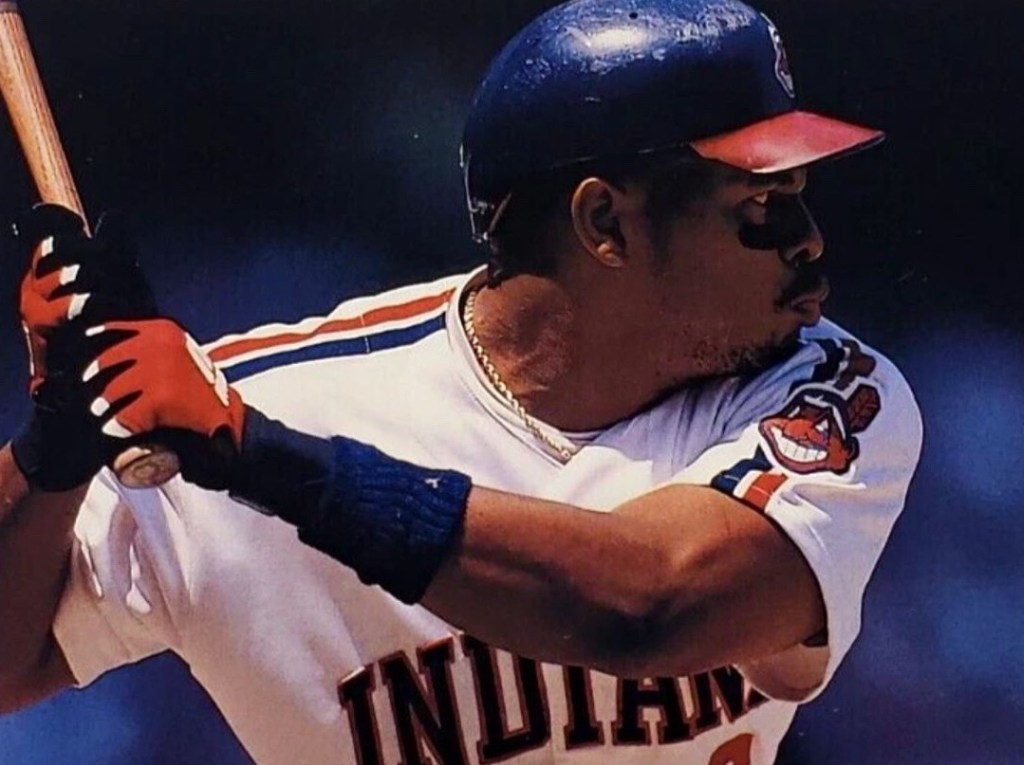

1. Albert Belle

The Algorithm’s Worst Nightmare

If you dropped Albert Belle’s early career numbers—1989 to 1992—into today’s scouting models, the verdict would be fast and cruel:

Inconsistent. Volatile. Maybe a fourth outfielder.

He played in just 224 games across four years. His OBP was average. He struck out more than he walked. He had a temper. And he was battling addiction.

By modern data standards, he’s a bust.

But from 1993 to 1998, Belle transformed into a machine—a statistical anomaly wrapped in rage and tape study. And the model didn’t see it coming.

Let’s run the numbers:

295 HR, 949 RBI in 8 full seasons Five straight 100+ RBI seasons The only player in MLB history with 50 home runs and 50 doubles in the same season More total bases in the 1990s than Ken Griffey Jr.

Yet no MVP. No Hall of Fame. No brand deal.

Why? Because Belle didn’t play the narrative game.

He didn’t pose. He didn’t apologize. He didn’t smile on cue.

What the spreadsheet misses is this:

Belle prepared harder than almost anyone.

He scouted pitchers personally.

He watched film obsessively.

He studied release points, tendencies, first-pitch patterns.

He was known to memorize scouting reports and visualize at-bats the way a quarterback runs through film.

Manager Mike Hargrove said:

“I haven’t seen a better hitter than Albert in a long, long time,”

Belle didn’t defy the data. He mastered it. But he didn’t let it define him.

And the system didn’t know what to do with that.

He wasn’t efficient.

He was relentless.

He didn’t chase WAR.

He crushed pitchers.

So yeah—Moneyball would’ve missed Belle. Because Albert Belle didn’t fit the model.

He beat the model, and the model hated him for it.

From 1989–1992, Belle’s numbers were erratic. He bounced between the minors and majors. He was intense. Volatile. Unmarketable.

By today’s model? He’d be cut.

But from 1993–1998? He was a wrecking ball:

5 straight 100+ RBI seasons The only player in history with 50 doubles and 50 home runs in a season One of the best right-handed power hitters of the modern era

He didn’t just hit. He studied. Obsessed. Prepared like a quarterback breaking down tape.

But because he didn’t smile for the camera, the system buried him.

2. David Ortiz

The Twins gave up on him. He was inconsistent, slow, and didn’t walk enough.

Then Boston signed him. And all he did was become:

- The most clutch postseason hitter of his generation

- A .688 OPS October monster

- The face of a franchise that broke an 86-year curse

- Our beloved “Big Papì”

Moneyball would’ve seen a strikeout-prone DH.

Reality saw a World Series hero.

If David Ortiz came up today—or worse, if he came up through the Oakland A’s front office during the Moneyball era—he never would’ve made it. Not as a star. Not as a franchise anchor. And sure as hell not as a postseason legend.

Let’s start with the basics. When Ortiz was traded from the Mariners to the Twins in 1996 (as “David Arias”), he was a big-bodied prospect with some raw pop, a long swing, and no clear defensive position. He wasn’t fast. He didn’t grade out well with the glove. And he wasn’t a high-OBP guy. In fact, through his first six seasons in the majors with Minnesota, he posted just a .348 OBP and never hit more than 20 home runs in a season.

In the eyes of a data-first front office obsessed with walks and glove-first value, Ortiz was a tweener. Too slow to play the field, not disciplined enough to fit the new gospel of on-base percentage, and without enough consistent power to justify a DH slot. The Twins released him outright in December 2002.

That’s right: released. Not traded. Not retained on a cheap deal. Let go, for nothing. If a Moneyball GM had been in charge, they might’ve even cited the stats to justify it. Too many strikeouts. Inconsistent splits. Low Wins Above Replacement (WAR). No defensive value.

But baseball is more than numbers.

Ortiz signed with Boston for $1.25 million. In 2003, he hit 31 home runs. In 2004, he became a Boston icon by helping end the Curse of the Bambino. And from there, he put together one of the most terrifying postseason résumés in history—three World Series rings, 541 career home runs, and a Hall of Fame induction.

Now let’s be honest: the stats eventually caught up. His advanced metrics became Hall-worthy after his game matured. But the point remains: a system like Moneyball—rigidly focused on immediate efficiencies and undervalued market metrics—would’ve kicked Ortiz to the curb before he ever had a chance to become Big Papi.

Why?

Because Big Papi didn’t project well.

He didn’t optimize early.

He didn’t look the part.

He was a bad fit on paper—but an all-time great on the field.

The Moneyball system, by its own logic, was built to extract value from overlooked players like Ortiz. But ironically, it would’ve missed him. Because what he needed wasn’t a spreadsheet; it was belief. It was coaching. It was mentorship, patience, and the right clubhouse.

Terry Francona famously let Ortiz be himself. Manny Ramirez hit in front of him. Boston gave him the leash to fail, the role to thrive, and the stage to become larger than life. No algorithm predicted that. But people saw it—eventually.

Ortiz is living proof that raw tools and personality sometimes matter more than launch angle or defensive runs saved. He was a clubhouse guy. A pressure player. A big moment magnet. You can’t model that on a laptop in Oakland.

In the Moneyball era, teams were terrified of DH-only players with low OBP. Ortiz became that archetype’s exception. But it’s worth asking—how many others like him were passed over? How many were reduced to decimals before they became legends?

David Ortiz was more than a stat line. He was heart, myth, and thunder—something the spreadsheet never saw coming.

Randy Johnson

Early in his career, Randy was wild. Couldn’t locate. Walked everyone.

Moneyball would’ve seen inefficiency. Volatility.

Then he figured it out. And became:

A 5-time Cy Young winner The most terrifying pitcher alive A 6’10” flamethrower who made hitters bail out before the ball left his hand

You can’t algorithm fear.

Randy Johnson wasn’t supposed to make it. He wasn’t polished. He wasn’t efficient. And early on, he sure as hell wasn’t effective.

He was 6-foot-10, all limbs and violence, hurling fastballs that no one could track—not even himself. He walked 120 batters in his first full season. He led the league in wild pitches. He had control problems so severe that one scout said, “He’s either going to kill somebody or figure it out.”

In a modern, Moneyball-style system, Randy Johnson wouldn’t have survived. Not as a top pick. Not as a rotation mainstay. And definitely not as a long-term investment.

Because Moneyball doesn’t like volatility.

It doesn’t like inefficiency.

And it definitely doesn’t like 6-foot-10 chaos merchants with 1.5 strikeout-to-walk ratios and zero pitch control.

If Randy Johnson had come up through a front office fixated on BB/9 and WHIP, he would’ve been buried in Triple-A—or shipped out as a failed project. At 25 years old, after four big-league seasons, he still had a career ERA over 4.50. His WAR was below replacement level. And yet, within five years, he would become the most terrifying pitcher of his generation.

The transformation didn’t come from a spreadsheet—it came from Nolan Ryan.

During a bullpen session in 1992, Ryan watched Johnson throw and noticed his head was flying open too early. He taught him to stay closed, to finish downhill, to harness the chaos. That simple mechanical fix—along with a mentality shift—changed everything.

By 1993, Johnson was an All-Star. By the late ’90s, he was practically mythological.

Over the next decade, he struck out over 300 batters in a season six times. He won five Cy Young Awards. He led a small-market team to a World Series. And at 40 years old, he threw a perfect game.

Moneyball would’ve flagged him for inefficiency. Too many pitches. Too many walks. Too old-school.

It would’ve questioned his delivery.

It would’ve doubted his makeup.

It would’ve missed the ceiling entirely.

Because Johnson was the exact kind of player the model avoids: high-risk, low-floor, “project” types. Guys who don’t grade cleanly. Guys who break molds rather than conform to them.

The sabermetric crowd often praises what a pitcher is now, but undervalues what a pitcher could become. Johnson was raw, terrifying, and unrefined—but inside all that unpredictability was a unicorn. You just had to be patient enough—and brave enough—to find him.

And even once he became dominant, Johnson still didn’t fit the Moneyball mold. He was high velocity, high strikeout, high pitch count. He worked deep into games. He didn’t rely on bullpen matchups. He didn’t nibble. He imposed.

He was everything the efficiency model isn’t.

And yet—he won.

Repeatedly.

Violently.

Spectacularly.

What’s more, Johnson wasn’t just dominant—he was demoralizing. He made hitters quit. Ask John Kruk. Ask Larry Walker. Ask the bird he vaporized mid-pitch.

That kind of intimidation doesn’t show up in WAR.

Randy Johnson reminds us that greatness sometimes looks like madness at first. That the players who change the game don’t always fit the models designed to predict the game. That projection isn’t math—it’s vision.

Moneyball likes clean numbers. Johnson was dirty. Wild. Beautiful.

And if the sport had followed the spreadsheet, we never would’ve seen him.

4. Greg Maddux

Didn’t throw hard. Didn’t strike out batters like the flamethrowers.

But he had surgical control, an IQ off the charts, and a film obsession that modern data still can’t quantify.

Maddux beat you before the game started.

The model would have missed him—until he started humiliating lineups for two decades.

Too Ordinary to Model

Why the Moneyball System Would’ve Missed Greg Maddux

Greg Maddux didn’t light up the radar gun. He didn’t intimidate with size. He didn’t fit any traditional scouting archetype—and ironically, he also didn’t fit the Moneyball mold.

He just dominated.

Quietly.

Systematically.

Forever.

The problem with applying a Moneyball lens to Greg Maddux is that Maddux looked like a statistical darling—but he wasn’t the kind of player the model would’ve pursued. Not early on. Not at face value.

He threw 85–88 mph fastballs. He didn’t have a wipeout slider or split. His strikeout totals weren’t gaudy. He walked fewer hitters than almost anyone alive—but in the early days, that didn’t make headlines. There was no “spin rate” or “barrel percentage” to validate what Maddux did. He didn’t have one freakish tool. He had all of them—just at human speed.

The Moneyball philosophy aimed to find market inefficiencies. But in Maddux’s early years, he was the inefficiency—and the system wouldn’t have known how to value him. He wasn’t flashy enough to be a scouting darling. He wasn’t analytical enough, on paper, to be an early sabermetric target.

In fact, if you’re just looking at early-career stats, there’s not a single number that screams generational ace. Through age 24, Maddux had a 4.11 ERA and 531 strikeouts in 716 innings. He looked like a solid, mid-rotation starter. Not the guy who would win four straight Cy Youngs or finish with 355 wins.

But here’s what the spreadsheet misses: Maddux was baseball incarnate.

He studied hitters like a surgeon. He played chess while they played checkers. He knew what you were thinking. Then he threw something that made you feel dumb for thinking it.

And here’s the real kicker—he didn’t even try to strike you out. That wasn’t the goal. The goal was efficiency. Weak contact. Ten-pitch innings. Two-hour games. He didn’t play to the stats—he played to the scoreboard.

Which is why WAR doesn’t quite capture him.

Why strikeout-to-walk ratio doesn’t explain him.

Why even his legendary control undersells the truth.

Maddux was so good, so precise, that hitters swung at pitches they knew they couldn’t hit—just to avoid falling behind in the count. He pitched to contact not because he lacked power, but because he preferred it. It was faster. Cleaner. Smarter.

Moneyball, by contrast, is a reactive model. It finds value after it’s created. It retrofits logic to outliers. But Maddux wasn’t an outlier. He was a master hiding in plain sight.

Would he have been undervalued today?

Probably.

Because nothing about him was “toolsy.” He didn’t flash. He didn’t go viral. He looked like a substitute teacher and worked like a mechanic. In a world obsessed with velocity and vertical break, he’d be slotted in as a 4th starter. If you judged him by peripherals alone, you’d never guess he could beat prime Bonds with a 3–2 changeup that never left the bottom of the zone.

But that’s the point. Greg Maddux wasn’t just smarter than the hitters—he was smarter than the model.

He was the inefficiency.

And unlike so many stars who overcame bad metrics, Maddux weaponized baseball’s invisible metrics: psychology, anticipation, pace, humility. Traits you can’t track with an iPad in the dugout.

If Moneyball ran the league, someone would’ve told him he didn’t throw hard enough. That he needed to work on spin rate. That his ceiling was low.

And they’d have missed the most cerebral pitcher in the history of the game.

5. Ozzie Smith

A slap hitter with no power? Pass.

That’s what early sabermetrics would say.

But Ozzie saved runs. Saved games. Saved seasons.

His defense alone made him a legend. And only recently have advanced stats caught up to his true value.

In the early years of sabermetrics, defense was an afterthought. WAR hadn’t been refined to properly capture fielding value. Zone ratings were primitive. “Range factor” was a guess. And most models—then and now—don’t fully value what Ozzie Smith brought to a team.

On paper, he was a light-hitting shortstop with a career .262 average and just 28 home runs over 19 seasons. The model sees that and shrugs.

But watch the tape.

Ozzie redefined what it meant to play shortstop.

He didn’t just field—he performed.

He made diving backhand stabs on balls other shortstops didn’t bother chasing.

He turned double plays from impossible angles.

He made pitchers breathe easier just by being behind them.

And yeah—he did backflips on Opening Day.

He was called The Wizard for a reason.

What Moneyball misses is this: Ozzie didn’t just save runs. He killed rallies. He turned momentum. He made the crowd believe. And he made the other team doubt.

And even when modern defensive WAR finally caught up, it still underrepresents how much psychological value he created on the field.

You can’t model a player who made entire stadiums gasp twice a night.

You can’t spreadsheet a myth that wore a glove.

Ichiro

But he racked up hits like a metronome. Stole bases. Played Gold Glove defense. Threw missiles from the outfield. And became a global icon.

Moneyball would’ve doubted the profile.

The field couldn’t deny the performance.

Oil Can Boyd

Inconsistent. Unpredictable. Emotional.

But when he was locked in, he had style, edge, and rhythm the model couldn’t touch.

He was the kind of player you needed a pulse to understand—not just a spreadsheet.

Bo Jackson

This deserves a section of its own…

⚔️ The Bo–Belle Paradox

One broke bats for the camera. The other broke pitchers for keeps.

Bo Jackson is worshipped.

He struck out in nearly 40% of his at-bats, never hit 35 home runs, never stole 30 bags, and never posted a WAR higher than 3.6 in any season. But none of that matters.

Because Bo wasn’t a stat line—he was a story.

He hit moonshots.

He scaled walls.

He snapped bats over his knee.

He posed shirtless in shoulder pads and eye black for a baseball card that became a cultural icon.

He trucked Brian Bosworth on national TV.

Bo was a myth in motion.

But—what happens if Bo Jackson shows up in today’s scouting model?

He’s a “swing-and-miss risk.”

He’s flagged for “multi-sport distractions.”

He’s downgraded for “inconsistent plate approach.”

He’s labeled “high volatility, low contract control.”

And no MLB team would even let him play football.

By modern data standards, Bo isn’t a draft pick.

He’s a “project,” or worse—“a branding liability.”

But fans? They never needed the spreadsheet.

They felt Bo. That was enough.

Albert Belle took the opposite path.

He had the physical tools to play football—but chose baseball. Not just to play, but to dominate.

He studied pitchers. Watched tape like a quarterback. Hit at sunrise. Lifted like a linebacker.

He once drove across state lines to scout a pitcher before a playoff game.

And he delivered. Relentlessly. Quietly. Violently.

But because he didn’t play the PR game, he got buried by the system.

Bo got remembered because he made the model irrelevant.

Belle got forgotten because he made the model uncomfortable.

V. The Hobby Mirror

Moneyball didn’t just infect front offices—it bled into the hobby.

Vaults, pricing apps, and card platforms now treat players like data points.

They price cards using comps, algorithms, and estimated “model value.”

So what happens?

A Pop 1 jersey-numbered Albert Belle 24K sells for $930 at auction. But the algorithm lists it at $603—based on comps for lesser players like Matt Clement. Meanwhile, Clement’s card is listed at $400. Same set. Same grade. Not even close in impact.

That’s insanity. But it’s also predictable.

Because the system doesn’t understand obsession.

Or narrative.

Or fear.

It just sees numbers.

And numbers don’t feel.

VI. Give Me the Players the Spreadsheet Fears

The algorithm is powerful.

But it’s not prophecy.

It missed Belle.

It missed Ortiz.

It nearly missed Randy.

It would’ve benched Bo.

It would’ve doubted Ichiro.

It would’ve passed on Maddux.

It would’ve overlooked the rhythm of Oil Can Boyd.

It would’ve mistrusted the wizardry of Ozzie.

Greatness doesn’t fit the mold. It shatters it.

So don’t tell me what the model says. Tell me who the model fears.

Tell me who wakes up early to hit in silence.

Tell me who studies film after a loss.

Tell me who makes pitchers flinch—and card collectors lean forward.

Give me the players who break the system.

Because the future of the game—and the hobby—belongs to the ones the algorithm never saw coming.

Leave a comment