Albert Belle didn’t win Gold Gloves. He didn’t patrol center field. And he wasn’t known for robbing home runs or crashing into walls like a highlight reel waiting to happen.

So what?

Somewhere along the way, Belle’s defensive reputation went from “decent but intense” to “liability who hurt his WAR.” But the truth—like most things with Belle—is more complicated, and far less convenient.

What the sabermetric era failed to understand—or worse, chose to ignore—was that Belle didn’t need to look like a graceful outfielder to impact a game. He didn’t need the loping strides of a Griffey or the balletic balance of an Andruw Jones. He just needed a right arm like a trebuchet, a competitive engine that never shut off, and the kind of intimidation factor that turned baserunners cautious.

Let’s talk about what actually happened on the field.

A 16-Assist Cannon

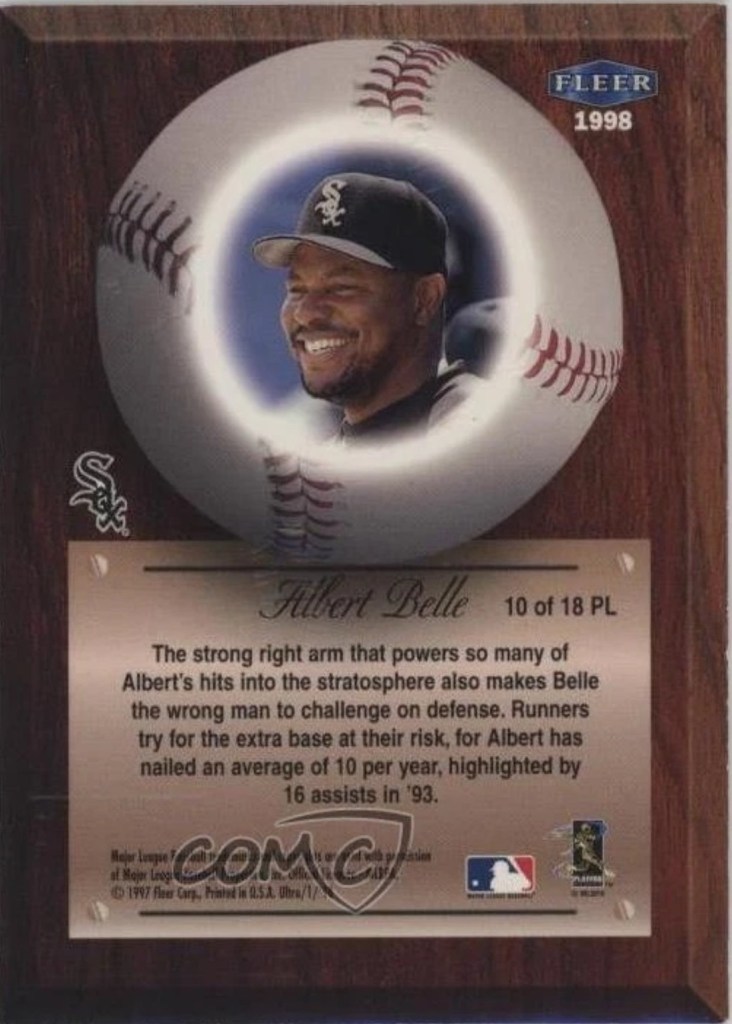

Baseball cards don’t always lie. The 1998 Fleer Ultra “Prime Leather” insert didn’t celebrate Belle’s 50-homer season, or his RBI titles, or even his violent swing. It talked about his arm:

“Runners try for the extra base at their risk, for Albert has nailed an average of 10 [assists] per year, highlighted by 16 assists in ’93.”

That wasn’t fluff. In 1993, Belle played 155 games and recorded 16 outfield assists, leading all left fielders and tying him for second among all outfielders in baseball. He wasn’t lobbing throws in—he was erasing runners. Turning second-and-home into inning-ending double plays. And after a few of those, guys stopped running.

And that’s the thing about arms. It’s not just about the assist totals—it’s about how many runners don’t even try anymore. The stat sheet doesn’t show the guy who stops at third. The WAR algorithm doesn’t know who held at second. But the opposing third base coaches? They knew.

What’s an Outfield Assist, Anyway?

An outfield assist happens when a player in the outfield throws out a baserunner—either directly or by starting a relay that leads to the out. Think of it as the baseball version of a laser pass that cuts down someone trying to score.

Common examples:

- A right fielder throws out a runner trying to stretch a single into a double.

- A left fielder guns down a guy trying to tag up from third.

- A center fielder throws behind a runner who took too wide a turn at second.

It’s not just about arm strength—it’s about accuracy, timing, awareness, and having a cannon that makes guys think twice.

And Belle had that. In spades.

Outfield Assists By Year: A Consistent Threat

Let’s run it down:

- 1991: 10 assists in just 123 games

- 1992: 9 assists in 131 games

- 1993: 16 assists in 155 games

- 1994: 7 assists in strike-shortened season (106 games)

- 1995: 10 assists in 143 games

- 1996: 7 assists in 159 games

- 1997: 7 assists in 153 games

- 1998: 8 assists in 163 games

Over his eight full seasons as a starting outfielder, Belle averaged over 9 assists per year. That’s well above league average. For context, in 2024, the MLB leader had just 12 outfield assists.

This wasn’t some fluke arm strength that showed up once or twice. This was a core part of Belle’s game.

The WAR Discrepancy: A Flawed Glance

So where did the narrative go sideways?

It starts with Wins Above Replacement (WAR)—a stat that, while useful in broad strokes, punishes Belle’s defensive contributions due to how it handles range and zone metrics.

Belle wasn’t a fast outfielder. He didn’t cover tons of ground. He didn’t rob homers or make diving grabs that SportsCenter would loop 12 times. WAR, especially in its early versions, put a huge premium on range and efficiency, and a huge penalty on players perceived to lack them.

But it didn’t know how to measure fear. Or momentum shifts. Or the psychological impact of a frozen runner at third base after Belle lasered one home the inning before. It didn’t credit him for the third base coach waving a runner and then pulling the windmill sign back at the last second.

Albert Belle had 16 OF assists in ‘93. Vlad never had that many in a season.”

— The Arm That Didn’t Count

Belle’s career dWAR (defensive WAR)? Negative. But what about all those games he changed without even getting a stat?

Manny, Vlad, Sheffield: Flawed, But Free

Let’s look at three guys often celebrated despite defensive flaws:

Manny Ramirez

Career dWAR: -11.7

Frequently mocked for poor defense, but never punished like Belle. He stayed on the field. Was treated as a lovable oddity. Even praised for his “baseball IQ” in some circles.

Gary Sheffield

Career dWAR: -28.3 (!)

Spent large parts of his career in the outfield despite being a worse fielder than Belle by almost every stat. Nobody’s keeping Sheffield out of the Hall for defense. It’s PEDs and a crowded ballot.

Vladimir Guerrero

Career dWAR: -9.9

But his arm? Legendary. Highlight reel. Everyone remembers “don’t run on Vlad.” Guess what? Belle had more assists in 1993 than Vlad ever had in a single year.

So what’s the difference?

Narrative. Charisma. Media love. And in Belle’s case—a lack of forgiveness. Because Belle wasn’t just flawed. He was angry and unapologetic about it. So when his defense showed any crack, it was treated like confirmation bias.

Misremembered Roles: He Wasn’t a DH

One of the most frustrating parts of Belle’s post-career discussion is the lazy fallback:

“Well he was basically a DH.”

Wrong.

Belle played 1,474 games in the outfield, compared to 255 games at DH. In his nine full seasons (1991–1999), he played the outfield in over 85% of his appearances. He wasn’t moved off the field until the last year and a half of his career, when injuries finally caught up.

A DH doesn’t rack up 16 outfield assists. A DH doesn’t intimidate baserunners. Belle was an outfielder—an average to above-average one—whose primary flaw was playing with a scowl instead of a smile.

The Defensive Double Standard

So why did Belle’s defense get painted as a negative, when guys with similar or worse numbers were allowed to keep hitting and be mythologized?

Because narrative is everything in baseball.

Belle had no relationship with the press. He didn’t smile for cameras. He didn’t give polished interviews. He didn’t participate in the soft-focus myth-making that turns hardball into bedtime stories.

So instead, people looked for reasons to discredit him. WAR gave them cover. Defensive metrics became an easy jab.

“He would’ve had more WAR if he wasn’t such a bad fielder.”

No—he would’ve had more WAR if the defensive metrics of the time knew how to measure what he actually brought. Like Vlad. Like Sheffield. Like Manny.

The Eye Test: What We Saw, What We Forgot

Watch the tape. The grainy ‘90s broadcasts. The laser throws to third. The high-speed relay to nail a runner at home. The power, the aggression, the fury.

Belle didn’t play defense softly. He didn’t jog to the warning track and toss the ball back in. He played the outfield like a linebacker covering the flat: aggressive, controlled, and ready to hit something.

His throws were hard. Accurate. On a rope. And he made runners pay. Every year. Quietly. Repeatedly.

Just because it didn’t end up on a Topps Chrome refractor doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.

Rewriting the Legacy

Albert Belle will probably never get the narrative makeover that so many players have post-retirement. He doesn’t do card shows. He doesn’t do interviews. He doesn’t play the Hall of Fame glad-handing game. And that’s fine.

But we can at least be honest.

He was not a defensive liability. He was not “just a DH.” He had a cannon arm that changed games. And he was every bit as impactful as his peers—who just smiled more while doing it.

If WAR is going to be the stat that defines a player’s legacy, it’s time to admit it got some guys very wrong.

Albert Belle is one of them. His bat alone was Hall of Fame-worthy. But even in the field, he wasn’t some docked liability. He was a threat—one that shows up in the game logs and box scores… if you’re willing to look past the myth.

Leave a comment