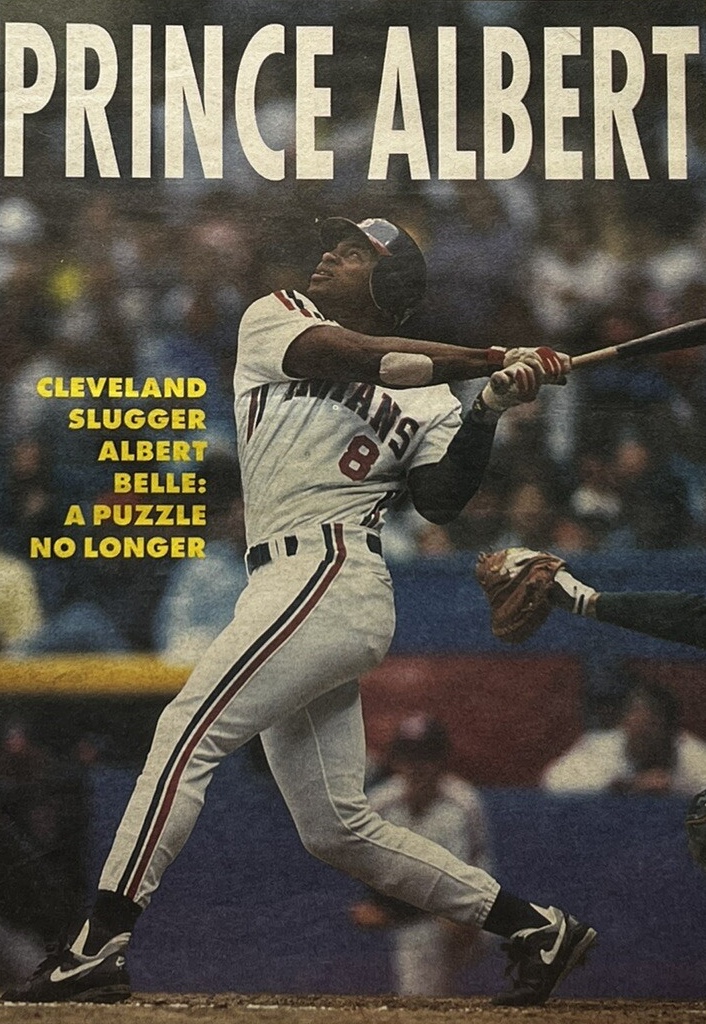

Cleveland Slugger Albert Belle: A Puzzle No longer

There’s more to major league home run leader than the past he’s left behind.

Alan Schwarz

Baseball America, 6/13/1993

WINTER HAVEN,Fla. — If anything can distract a man at work, it’s the hideous attempt that two Cleveland Indians make at harmonizing to a Tom Petty tune one batting-practice morning this March. The crooners, who plead successfully to remain anonymous, sway together a la Donny and Marie but can’t quite reach the crescendo of “Free Fallin’,”sending shivers throughout the cage.

Down. Down and away, coach.

Albert Belle hears nothing. He cracks no smile when hitting coach Jose Morales later complains of the “pot-smoking” Bad Company music crawling out of the Chain O’Lakes Park public-harass speakers, or when since-traded Mark Whiten hilariously undulates to the somber beat. Even the sun doesn’t mess with Belle. It hides behind the one cloud in the Florida sky.

The Cleveland slugger is working on hitting pitches the opposite way, and it doesn’t quite happen. Grounders to second,line drives that he knows would have stayed up a little bit too long.

This wimpy go-with-it style doesn’t come easy to him. His eyes need more focus than fury. Eight swings, and Belle punctuates the workout by slamming his club to the dirt.

Six hours later, the mountain of muscle slowly rises, wipes his mouth with his linen napkin and politely excuses himself from a pensive 45-minute dinner/interview. The gleam in his eye can mean only one thing: It’s hockey night at the Holiday Inn.

His Sega video game team is the Detroit Red Wings. He matches sticks on his hotel room television against fellow Indians Paul Sorrento, Wayne Kirby and Marty the club-house guy. Fittingly, Belle’s weapon of choice isn’t Steve Yzerman, a deft, dashing scorer, but Bob Probert, the Motor City’s resident goon.

“I change the lineup to put Probert in the game so he’Il knock out the other guy’s best player in the first period,” Belle says with a sinister grin. “He’Il knock out them out for the game. Nobody can beat him. Every time he gets in a fight, he wins.”

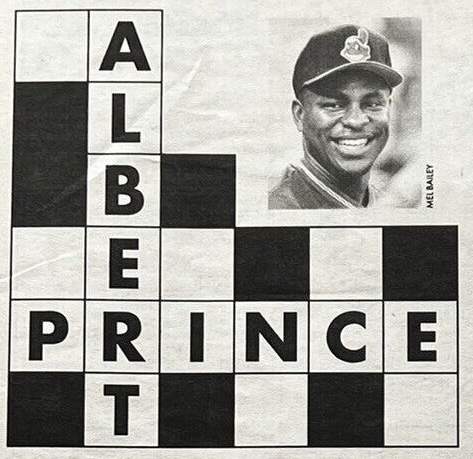

Subtlety never has been Albert Belle’s strong point. He crushes baseballs with the same sincerity with which he discusses everything from his crossword puzzle obsession to the fables of his sullied past.

He asks no understanding, no forgiveness. Just eight more low and outsíde.

Albert Belle’s discretion and the baseball public’s compassion for him have squeezed out of the same eyedropper. He long ago used up his get-out-of-doghouse-free cards. Hearing racial slurs was no excuse for ——SCREENSHOT LOST BOTTOM OF PAGE | ASSUME IT WAS NO EXCUSE FOR HIS ACTIONS ——

When Belle fired a ball in May 1991 into the sternum of a Cleveland Stadium fan, who had taunted the fresh-out-of-rehab Belle by inviting him to a postgame keg party, he bruised more than the guy’s gut. Belle returned from his week-long suspension and a subsequent 16-game disciplinary demotion to Triple-A Colorado Springs with his already questionable reputation set forever like clay fresh out of a kiln. He caught Dibble Disease.

Sixty-four home runs later, including 11 this season to lead the major leagues through May 9, Belle knows his baseball prowess can’t paint over the graffiti of his youth. He remains the Charles Barkley of baseball, a talented man whose actions, often louder than his words, follow him with a pointy trident that periodically has poked him into repeating history.

For all of this, though, Belle is no raving maniac, some Tasmanian Devil spinning out of control, buzzing through trees. His moody blues have obscured his intelligence and good nature.

The incident in Cleveland tripped a switch inside him. If moronic fans won’t let him forget his alcohol problem, maybe he could keep potential morons from getting sucked down a similar whirlpool. Belle since has been one of the Indians’ most active community speakers.

“I can pretty much talk from personal experience that alcohol certainly ain’t going to help you,” says Belle, 26, who left rehab asking to be known by his given name Albert instead of Joey, a shortened version of his middle name Jojuan,“You go into the community and talk to the kids. They have so many questions about life, about baseball, about peer pressure, about drugs and alcohol and stuff. I experienced that and still experience that. You try to show the positive side of saying no.

“As they’re growing up, their parents are beating into their heads to make good grades. They hear it so much. When we say it, they sometimes listen to us more.”

Belle’s is a familiar message, but one decorated with chilling detail. His drink of choice was a concoction named Gorilla’s Breath, equal parts 151-proof rum and 101-proof Wild Turkey bourbon. During his summer 1990 rehab, which took him 58 days instead of the prescribed 30 because he bolted once and remained headstrong through most of it, Belle heard a woman talk about snorting cocaine. A man and his heroin.

This wasn’t the major league life he dreamed of.

Many onlookers thought Belle never would reach the big leagues. His talent broke Louisiana State University records for home runs and RBIs, his temper the unofficial mark for sus… ——SCREENSHOT LOST BOTTOM OF PAGE—— Belle would be tantamount to resigning.

Belle’s powder-keg personality continued in the minor leagues, but the shaking heads just gave him more incentive.

“They said you can’t do that in the minors, and you can’t do that in the majors,” Belle says. There were scouts who said, ‘well, he’s not going to make it to the majors.’ I kind of used that to thrive on. I’m going to work twice as hard to make it.”

Belle’s resentment for the doubters left him anxious to bond with people outside of baseball. While almost all the Indians and the football Browns live on the west side of Cleveland, Belle set up shop on the east side. Some of his best friends are from his local church or people with whom he went through treatment three years ago. Others are fellow students at Cleveland State University, where Belle has taken courses each offseason to complete his accounting degree.

Maybe the guy is nuts. He actually likes accounting, and not just because those were the classes he and his fraternal twin brother Terry strategically selected at LSU for their late starting times. With little release available on the playing field, Belle had academics to turn to during his seemingly constant adversity.

His interest in education began with his parents, who both teach in the Shreveport,La., school system. For every fastball thrown in the back yard, there was a puzzle book or Scrabble game in the den. Albert and Terry each took 15 hours of college courses at LSU-Shreveport during their senior years of high school, many during baseball season. Now an accountant, Terry says he probably wouldn’t have become one had Albert not turned him on to the subject that year.

“I think it’s in Albert’s blood,” says their mother Carrie, who proudly adds that both Albert and Terry were Eagle Scouts. “A lot of people on both sides were very educated. There are medical doctors, teachers, lawyers.

“You could see it when we went on vacation. We went to the Houston Astrodome, the Lion Country Safari in Dallas. Albert loved maps. He’d outline where we were going with an accent pen, and directed us where to go. When he was 5, mind you.”

Belle’s curiosity lives today. While his dinner companion goes straight for the steak-and-shrimp combo, he orders the blackened grouper specifically because he has no idea what it is.

Then there are the crossword puzzles, the USA Today offerings Belle completes every day and the Sunday cryptomonsters for which he subscribes to the New York Times. He’s the undisputed crossword king of the Indians… ——SCREENSHOT LOST BOTTOM OF PAGE—— “…They’ve got all the operas, music composers—blah, blah, blah. I have no idea who they are. You go to the library and look up those guys.”

But don’t get the impression Belle sits around the clubhouse with a pencil above his ear and an encyclopedia in tow. There’s plenty of laughter around his locker, or at least until the press arrives. He and Kenny Lofton continually debate over whether Belle is good-looking.

“He’ll come out of the shower, look in the mirror and say, ‘I’m good-lookin’,’ ” Lofton says carefully, first darting his eyes to make sure Belle isn’t lurking nearby. “He always says he has the best body in America. That’s a mistake.”

“One year,” Kirby says, “he got hurt and broke his jaw. Everyone was like, ‘Damn, Albert, you look like Mike Tyson now. You’re missing a couple of teeth.’ He wanted to laugh, but his mouth was all wired up.”

Belle pretty much has let his bat do the talking since. No place is better for a fresh start than Cleveland, where a roster metamorphosis leaves only Felix Fermin and Joel Skinne around from when Belle reached the majors in 1989. Fan enthusiasm for the Indians is at an all-time high, what with a new baseball-only teepee called the Gateway coming next year and almost every one of the team’s key young players signed to long-term contracts.

Not surprisingly, getting Belle’s name on the dotted line prompted headaches and headlines this spring. He finally came to terms March 4 for three years and $8 million, giving him plenty of numbers to play with on his balance sheets. It also afforded a stability he never had experienced.

“When I signed my multiyear deal, everyone was excited, coming over and congratulating me,” Belle says. “You feel like part of the family because the other guys signed. If I didn’t like being around these guys or being in Cleveland, I wouldn’t have signed.I wouldn’t have moved here.

“There was a lot of media: You’re not going to see Albert in an Indians uniform again, they should get rid of him. Blah, blah, blah. The Indians went out on a limb to get me. Now that it’s worked out, I can back it up by putting up big numbers.”

Leave a comment